Lifelong learning (LLL) has become a cornerstone of national and Higher Education institutions’ LLL-strategies. Yet current offerings often appear fragmented, leaving learners with limited flexibility to create personalized learning pathways aligned with their unique skill levels. The national strategy for lifelong learning in Finland (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2022), national Digivisio2030 project (Digivisio2030) and the development of microcredentials has challenged higher education institutions to critically evaluate existing approaches and practices for organizing education in a learned-centered way. How should we design LLL offerings, including microcredentials to better address the individual needs of learners and the rapidly changing skill requirements of the world? What old ways of thinking should we challenge to make redesigning and accessible personalized learning pathways possible?

Based on collaborative development work with five Universities of Applied Sciences, we propose a cultivated approach to microcredentials (Laine, Juuti, Oksanen, Rokala & Marin, 2024). Our vision emphasizes modular microcredentials structured around a competence-level framework. This learner-centered model enables individuals to stack interdisciplinary competencies, thereby broadening their knowledge or deepening their expertise. Designed to serve the needs of lifelong learners, these microcredentials provide purposeful pathways through diverse educational offerings.

Defining competence for lifelong learning

The current EQF level descriptors (levels 6–7) primarily support formal degree structures and do not adequately address the needs of lifelong learners or the labor market. To complement these frameworks, a more learner- and labor market-oriented way of defining competence levels is needed. Standardized, transparent descriptions of competences help both learners and employers to better recognize and understand the skills and knowledge acquired through microcredentials.

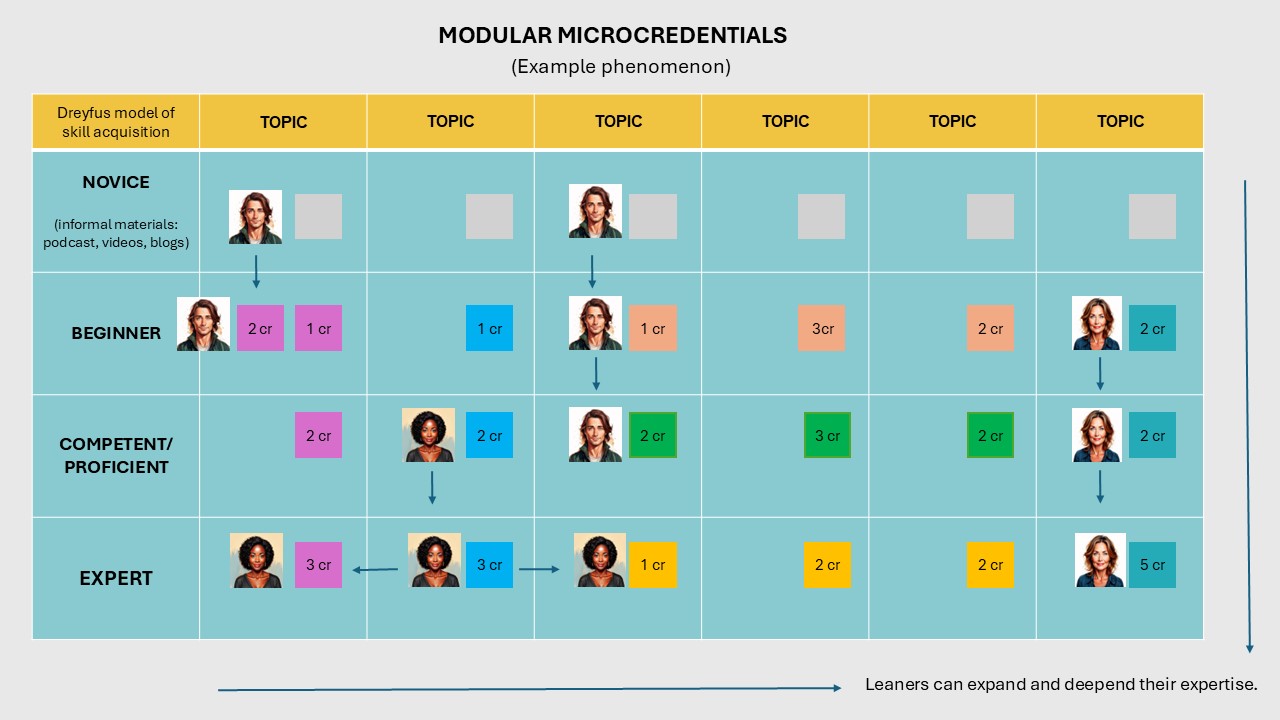

To support this, we apply the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to define skill levels, as reflected in Standard Information Element 9 of our National Framework (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2022). This model offers an intuitive structure for classifying competence development in a clear and accessible manner.

This approach is important for several reasons. First, it enables reliable assessment by allowing higher education institutions, employers, and learners themselves to evaluate competencies in a consistent and transparent way. Second, it fosters learning progression, providing structured pathways for development and helping learners visualize their growth. Finally, it facilitates academic recognition by aligning skill levels with the national qualifications’ framework, thus enhancing the credibility and transferability of microcredentials across educational and professional contexts.

Modular microcredentials and stackable competence

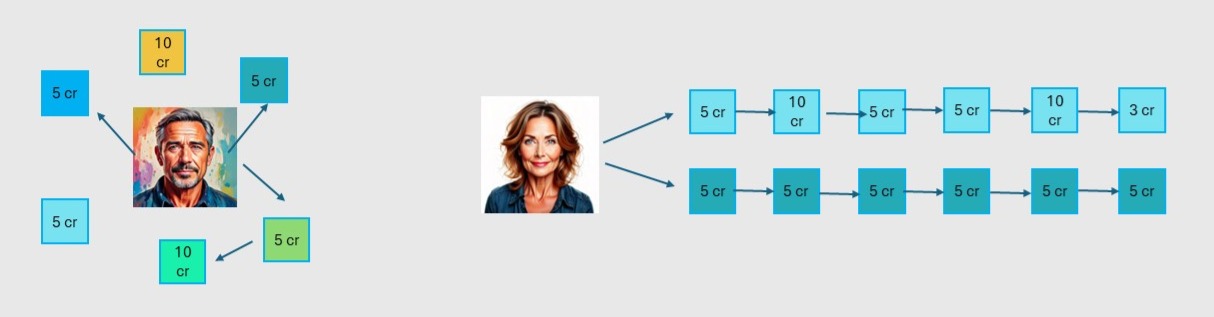

Currently, the lifelong learning offerings of higher education institutions in Finland appear fragmented and disconnected to learners. Learners do not have a clear understanding of how and where they can accumulate and stack their competencies in alignment with their individual skill needs. Higher education institutions have also designed predefined learning pathways for lifelong learners to help them develop and update their skills. However, from the perspective of lifelong learners, these are often composed of modules that are too large or include a “forced” sequence of completion. This creates a risk that learners may be required to study something they already know, which may cause frustration, which may, in turn, result in them giving up? In our view, this approach fails to adequately consider the individual skill levels and needs of learners. Picture 1 below illustrates this discrepancy.

In our view, microcredentials should be designed to be modular and constructed from smaller components than they currently are. This would give lifelong learners more freedom to create learning pathways that are meaningful to them and aligned with their individual skill needs. As mentioned earlier, microcredentials could be also designed with a focus on skill-level thinking, as seen in picture 2.

The structure depicted in Picture 2 helps learners better understand the various opportunities for expanding their skills horizontally (broadening knowledge) or deepening their expertise in a specific phenomenon vertically (specializing). Ideally, a lifelong learner would recognize their own starting level of competence and identify studies that align with it, avoiding the need to complete something they already know. Microcredentials designed in this way allow learners to develop meaningful, stackable and interdisciplinary competences tailored to their unique needs. (Marin, Oksanen, Juuti, Laine & Rokala 2024.)

Designing modularized microcredentials requires harmonization in describing learning outcomes

Designing modularized microcredentials calls for a shift in how higher education institutions to conceptualize and describe learning outcomes. While the current EQF level 6–7 descriptors effectively support traditional degree structures, they fall short in addressing the evolving needs of lifelong learners and the dynamic demands of the labor market. Insights from our development work reinforce the idea that adopting a more labor market-oriented approach to defining competence levels not only benefits institutions in designing microcredentials, but also supports learners in constructing meaningful, stackable learning pathways (Marin etc., 2024).

A more unified and concrete articulation of competence—as suggested in the EQF’s triad of knowledge, skills, and responsibility/autonomy—can enhance the ability of learners and labor market actors to identify, recognize, and communicate the value of acquired competencies. In this context, standardization plays a pivotal role. Harmonized descriptions of competencies and their levels across higher education institutions would not only improve comparability but also enable more effective AI-assisted guidance for lifelong learners on digital platforms. Preliminary experiments support this notion, indicating that AI can facilitate consistent articulation and alignment of competencies, thereby bridging institutional and national differences (Oksanen, Marin, Kuitunen, Laine & Rokala, 2025; Laitinen & Wallin, 2023).

Despite decades of emphasis—more than 60 years after Bloom’s taxonomy—crafting clear, measurable learning outcomes remains a persistent challenge. The way we define and write competencies has far-reaching implications: it directly influences stackability, cross-institutional and international recognition, and the meaningful transfer of skills. Overly broad or overly rigid outcome statements may fail to reflect what learners can actually do, focusing instead on what has merely been taught. This disconnect raises essential questions: Do our learning outcomes truly capture real-world capabilities? Are they aligned with employer expectations? And how can we ensure that outcomes are defined with the clarity required for quality, credibility, and recognition?

Ultimately, formalizing microcredentials adds significant value. As governments, universities, and employers increasingly recognize them, microcredentials gain both credibility and impact, offering a legitimate and flexible means of validating skills in a changing educational and professional landscape.

Building future skills through microcredentials

Higher education institutions are still defining their role in a world where lifelong learning is no longer optional but essential. In this evolving landscape, micro-credentials are a key response to the shifting demands of the labor market. Microcredentials help professionals stay competitive, but they can also act as an entry point to education and a gateway to employment for those who are just starting out. Micro-credentials are changing the way we learn, offering flexible, needs-based learning opportunities that challenge traditional models.

Partnerships play a critical role in creating modular microcredentials. Strong collaboration between higher education institutions, employers, and other stakeholders is essential to ensure that micro-credentials fulfill their promise—as recognized, stackable, and impactful tools that bridge education institutions, learners and labor markets.

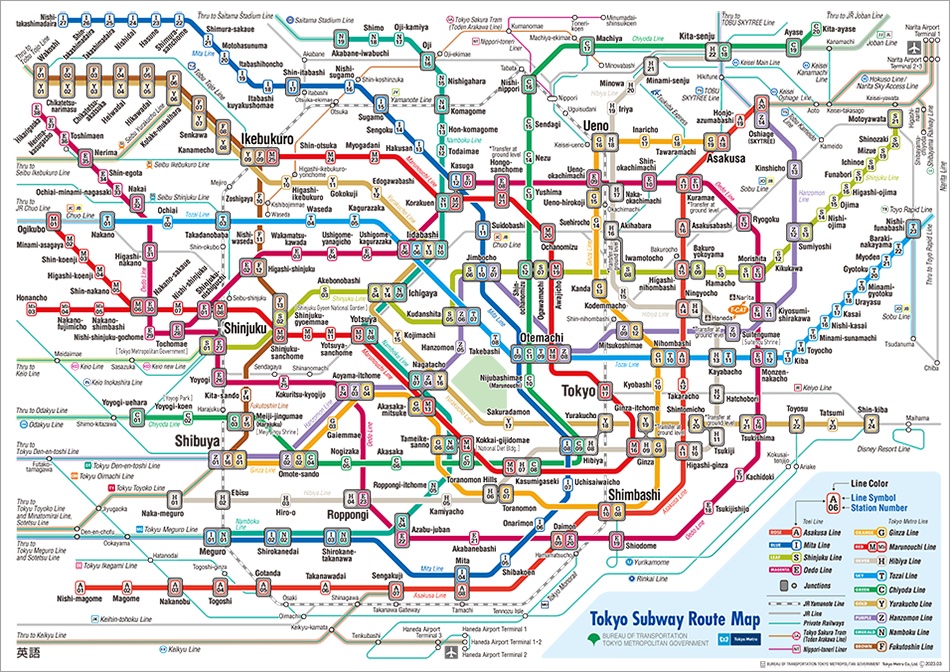

Are we, as higher education institutions, ready to design microcredentials with a more learner- and labor market-oriented approach? Are we willing to relinquish a certain degree of institutional autonomy to harmonize our ways of describing learning outcomes and to incorporate more labor market-oriented nuances into competence level descriptions? Are we prepared to develop new practices to support lifelong learners navigating the offerings of microcredentials across different educational institutions nationally and at the EU level, crafting their unique learning pathways—much like navigating the Tokyo metro map?

We believe it is possible — but it demands collaboration and a shared understanding of the foundations of microcredentials. To navigate the profound transformations of our time, we need a collective commitment to reimagining our mindset and boldly co-creating new learning pathways that respond to the needs of a rapidly changing world.

References

Digivisio2030.Front page – Digivisio2030.

Laine, K., Juuti, N., Oksanen, V., Rokala, K. & Marin K. 2024. Ammattikorkeakoulujen yhteisen koulutuskokonaisuuden muodostaminen vaatii yhteistä ymmärrystä ja yhdessä tekemistä.

Laitinen, A. & Wallin, O. 2023. Osaamisen kuvaustiedon kokonaisuus. Esiselvityksen raportti. Digivisio2030.

Marin, K., Oksanen, V., Juuti, N., Laine, K. & Rokala, K. 2024. Jatkuvalle oppijalle suunnattu koulutus tarvitsee uudelleen muotoilua ja modularisointia. Jatkuvalle oppijalle suunnattu koulutus tarvitsee uudelleen muotoilua ja modularisointia – Hiiltä ja timanttia

Ministry of Education and Culture 2022. Kansallinen korkeakoulujen jatkuvan oppimisen strategia 2030. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö. Maailman osaavimman ja sivistyneimmän kansan kotimaaksi

Ministry of Education and Culture 2024. Pienten osaamiskokonaisuuksien viitekehys/luonnos 2024. Työryhmäraportti. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö. Microsoft Word – Pienet osaamiskokonaisuudet linjaus huhtikuu 2024.docx

Oksanen, V., Marin, K., Kuitunen, H., Juuti, N., Laine, K. & Rokala, K. 2025. Yhtenäinen osaamisen kuvaaminen: selkeyttä oppijalle – uusia mahdollisuuksia korkeakouluille.

Author

-

Kati Marin

Specialist, Metropolia University of Applied SciencesKati Marin, a specialist in continuous learning, develops new learning support solutions for higher education institutions that address the evolving needs of working life and, consequently, the changing continuous learning needs of individuals.

About the author -

Virve Oksanen

Expert and developer in the field of lifelong learningMaster of Arts degree and is a qualified subject teacher, Laurea University of Applied Sciences

About the author