A safe and inclusive learning environment is one of school’s key objectives, as it supports the well-being, learning, and sense of community of both students and teachers. The importance of inclusion and psychological safety cannot be overemphasized. Positive interaction between students and teachers plays a key role in shaping the school climate, which in turn has a direct impact on learning. (Ihamäki, Nuutinen 2024, 4-5.) To address these themes, this article introduces both theoretical perspectives and practical approaches to enhancing interaction in schools, with the aim of supporting meaningful learning and growth.

In a welfare society, the target is to ensure equal participation for everyone in education. Supporting children in the early stages is especially important, as it helps them to identify their resources and strengths and take part in community building in a positive way. Some children have weaker starting points, but school is supposed to be a safe place for all with its routines and equality. The well-being of teachers and children can be taught, learnt and fostered to generate positive feelings.

To develop positive learning experiences for all students in comprehensive schools, Finland, Latvia and Estonia joined forces in the project Breaking Barriers. The schools in all the three countries share common challenges and goals. In this article, we focus on describing the implementation of the project in Finland. In Finland our goal was to support subject teachers, who teach students from an immigrant background and need special education in lower secondary schools. As the project progressed we realized that the same measures that are necessary to support students with special needs also support all students and teachers. All activities were theory-based, and knowledge and observations were generated in workshops and through practical monitoring and cooperation between teachers and students in lower secondary schools. (Ihamäki, Nuutinen 2024, 4-5.)

The target group of the project Breaking Barriers were students in need of special support and with immigrant backgrounds as well as teachers and other staff in two lower secondary schools in Haaga and in Vesala in Helsinki. A total of four workshops were conducted during the project, two for students with immigrant backgrounds and receiving special support and two for teachers in both schools. (Ihamäki, Nuutinen 2024, 4-5.)

Inclusion as foundation for equal learning opportunities

The United Nations has recognized the importance of inclusion in schools. Inclusion consists of the idea of appreciating the diversity of students and supporting learning for all. (Salamanca 1994; Sirkko, Takala, Muukkonen 2020.) Inclusion means that all students regardless of their backgrounds and their special support needs study together at least some part of their studies in ordinary Finnish schools. This means that students who need individual support are full members of the general education group, even though they are taught in a different way. Support can be provided through the cooperation of a pair of teachers, part-time tutoring, partly in small groups or through other support methods. (Cf. Alajoki 2021, 14.)

How different professionals strengthen education

In multi-professional teams, professionals from different backgrounds work together to implement the tasks their work demands. Typically, multi-professional collaboration takes place in a team format. The team is a stable structure of collaborative practice in which each professional works together in a way that contributes to the whole. In teamwork, diverse competencies of members and expertise are valued (see Peleman et al., 2018; Salas et al., 2003.)

Our team in the Breaking Barriers project in Finland was multiprofessional and we made all decisions together. The participants included two special education teachers in Lower Secondary Schools in eastern and western parts of Helsinki, two senior lecturers in Social Science and Health Care Leadership at Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, and a Graphic Designer. Our cooperation proved to be meaningful and beneficial with each participant bringing their unique perspective and knowledge to the project. The teachers provided instructions, acted as facilitators and led reflection discussions in the workshops. In addition, the teachers planned themes and analysed the results of the workshops based on positive psychology.

Multiprofessional work is fruitful when everyone contributes their knowledge from different professional backgrounds and experiences to the project. Our collaboration consisted of multiprofessional meetings with the participants in Helsinki, four workshops and visits to two lower secondary schools in Helsinki as well as international and national seminars.

© Eeva Louhio

The practical arrangements for a safe environment were decided by all participating teachers. All themes and activities in the workshops were based on select theories. The graphic designer created the posters/announcements for the project and played a role in documenting the workshops visually. She created drawings to capture key moments, interactions, and activities during the workshops and to express something that is challenging to convey through words. The designer’s role in the documentation was independent and she was able to decide herself what kind of pictures were needed. The work was straightforward and working with other project members easy. The graphic designer played a crucial role in the project, creating posters and announcements that visually represented the project’s goals and outcomes.

Managing safety in schools

Educational theories examine and support the construction of a safe and resilient environment in the school and the classroom. Fostering comprehensive safety helps to support the well-being of students and teachers. As safety is closely linked to overall well-being, it is essential to explore proactive measures for its improvement. The comprehensive safety management model for education outlines proactive safety management of challenging situations, the handling and follow-up of such situations as well as shared learning. By using this model, safety management will turn into systematic, shared action with lasting results. (Hollnagel 2014.) The safety themes discussed in the workshops extended also to the strengths, needs and wishes of the teachers and students.

Appreciative inquiry and its role in safe learning environments

Appreciative Inquiry is a positive, teamwork-focused approach to improving organizations and education. Instead of looking for problems, it highlights and builds on the strengths within a system (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1999; Cooperrider, Whitney & Stravos, 2008). This method has gained recognition for fostering inclusive and psychologically safe learning environments, especially in diverse educational settings.

Appreciative Inquiry works through a four-step process:

- discovery

- dreaming

- designing

- delivering

This process encourages participants to recognize their strengths and envision a better future based on shared values and goals (Whitney & Torsten-Bloom, 2010). Appreciative Inquiry supports the principles of inclusive education outlined by UNESCO and the Salamanca Statement (1994) by promoting participation, fairness, and valuing diversity in the learning process.

Many researchers recognize Appreciative Inquiry as a valuable tool for organizations looking to create positive change and foster a culture of growth (Cooperrider, Whitney & Kaplin 2005). By spotlighting positive aspects, significant improvements can be realized, linking Appreciative Inquiry to the principles of positive psychology (Heikkinen et al. 2023, 88–89).

This form of action research highlights the inherent goodness and potential of organizations (Cooperrider et al. 2008). Unlike traditional approaches that often dwell on weaknesses and obstacles (Bushe 1999), Appreciative Inquiry encourages a mindset of ongoing learning and improvement, encouraging organizations to view themselves through a “positive lens” (Hammond 2013; Reed 2007). The method focuses on uncovering resources and opportunities by asking positive questions. It emphasizes teamwork and inclusion to drive change (Cooperrider & Srivastva 1999; Cooperrider, Whitney & Stravos 2008; Whitney & Torsten-Bloom 2010).

In the Breaking Barriers project, Appreciative Inquiry was a powerful tool for creating positive learning experiences in lower secondary schools. By involving students, teachers, and school staff in conversations about their skills and aspirations, the project helped create an inclusive environment where everyone was encouraged to voice their opinion in shaping their learning community. By using Appreciative Inquiry, the project’s workshops shifted away from focusing on what was lacking and instead encouraged a culture of exploration and collaboration. This allowed both students and educators to discover their strengths, share their needs, and work together to create strategies for improving well-being and engagement in schools. The results show that this method not only promotes inclusion but also enhances psychological safety by encouraging open communication, respect, and a shared commitment to continuous improvement.

By incorporating Appreciative Inquiry into teaching practices, schools can establish sustainable models for inclusive education that empower students and teachers. This process nurtures a sense of ownership, agency, and resilience, which are essential for supporting students from immigrant backgrounds and those needing special education. The focus is on positive inquiry and community-building, which can drive lasting change, reinforcing the importance of holistic and student-centered educational strategies in creating safe and inclusive environments in lower secondary schools.

Hearing students and teachers through interactive workshops

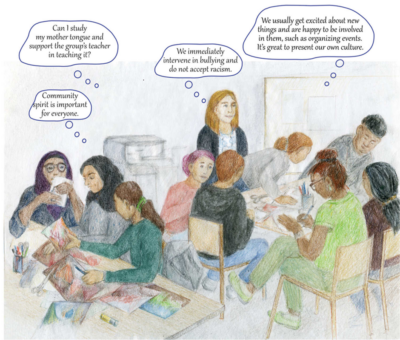

The project aimed to identify suitable targets and methods for developing functions and activities in schools through workshops. During the workshops, students with immigrant backgrounds and those receiving special support in grades 7–9 worked on themes related to strengths, support, needs, and wishes. The same goals were set for the participating teachers. The same themes guided the work of the participating teachers. All participants had the opportunity to share their perspectives and be genuinely heard.

The atmosphere in the workshops was positive. The graphic designer’s work in the project proved to be valuable as she discovered many interesting perspectives through observation. In the workshops, special education teachers held a dual role: they acted as facilitators in the student group and participants as peers in the teacher group. The graphic designer also gained valuable insights into the situation of young people with immigrant backgrounds as well as up-to-date knowledge about current school practices. Illustrations depicting key theoretical perspectives and related situations helped all participants better understand the project.

The teachers and students discussed various questions freely, and the conversation could be described as fruitful, open, and appreciative of different perspectives. Teachers, who were members of the project, facilitated the group, gave instructions, and took notes during the discussions. The teachers and students expressed their gratitude for the time devoted to working together and the opportunity to participate.

Creating a warm and welcoming atmosphere for every student

A warm and welcoming school environment begins with the teacher. When teachers adopt a supportive, coaching-oriented stance and respond non-defensively to questions and challenges, they foster a climate of psychological safety. In such environments, both students and staff feel accepted and respected, even in the face of mistakes or uncertainty. If teachers act in authoritarian or punitive ways, students may be reluctant to engage in the interpersonal risk involved in learning behaviors such as discussing errors. (Edmondson 1996.)

© Eeva Louhio

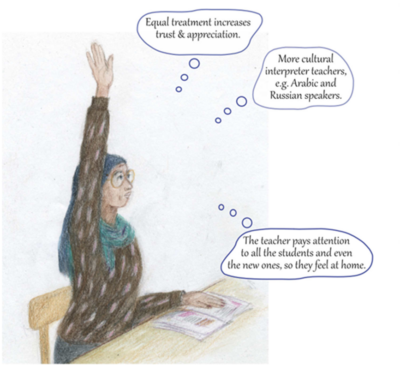

Teachers play a significant role in developing young people’s self-esteem, activity and participation. To determine the most effective teaching methods, teachers must first understand each student. Conversations, observations, written interactions, and personal engagement all contribute to this understanding. In communication, pathic perceiving refers to the ability of teachers to be present and sensitive to the full range of students’ emotions, expectations, and experiences.

Teachers’ pathic acting, in turn, reflects a teacher’s deep understanding of students, openness to experiences, and sensitivity to individual situations. Pathic interacting emerges in the way in which teachers intuitively, reflectively, approvingly and informatively negotiate and communicate with students, both verbally and non-verbally. Teachers support the students’ sense of autonomy, relatedness and competence in learning situations by allowing them appropriate freedom and responsibility. In addition, they foster an open atmosphere in the group by building caring relationships and encouraging a sense of ownership through pedagogical sensitivity. When students are allowed to experience and reflect on their own emotions in a safe environment, it strengthens their personal growth and contributes to the development of the wider school community. (van Manen & Li 2002; Saariaho 2023.)

Building trust is an important ingredient in creating a climate of psychological safety. While trust alone may not guarantee a climate of mutual respect and care, it lays the groundwork for developing interpersonal confidence and taking the kinds of risks that define psychological safety. (Edmondson 1999.)

© Eeva Louhio

The pedagogical principles discussed above were put into practice during the project. The materials from the student workshops were analysed and presented in the teachers’ workshops. Based on the analysis, the teachers started to collaboratively develop their practices and formulate further recommendations during the workshops aimed at fostering a warm and welcoming atmosphere in their classrooms. Many development ideas emerged such as how to better respond to students from different backgrounds, how to customize and personalize teaching in easy Finnish, how to visualize teaching and use images and how to define concepts as well as how to define concepts in different ways and thus ensure learning. Additionally, language awareness pedagogy – i.e. the understanding of how language works and impacts learning – was considered, highlighting its importance in teaching and activities at all levels of education.

According to the teachers, they need more information and education about cultural sensitivity, for instance how to teach sensitive topics such as sexuality to immigrant students. Schools should also organize multicultural days, led by students and involving families. This was seen to strengthen diversity and community building in the school environment. In addition, students expressed a need for stricter rules and guidance in schools because some of the students join gangs at a very young age. According to the students, sufficient discipline and advice would help students avoid connections to gangs.

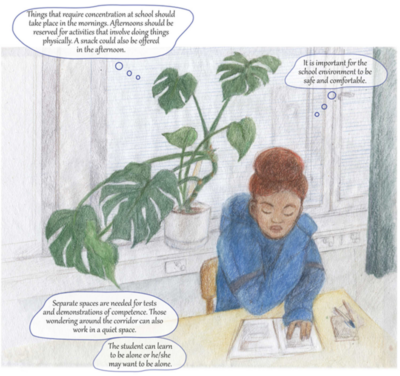

Life management and learning can be supported in many ways. There are various forms of support available to teachers and other staff in schools, including team meetings, studies for socioemotional skills and so forth. Both teachers and students felt that quiet spaces were important for calming down, supporting differentiated instruction and learning to be alone. The importance of permanent spaces was also highlighted. The presence of nature in the school was felt to create an aesthetic and calm atmosphere. Having plants and animals in the school made students want to work near them, and for some of them this was an important reason for coming to school. They also cared for the plants and animals, which allowed them to express their strengths and sense of environmental responsibility. Even small details, like green plants, can make a significant difference to well-being.

Lessons from breaking barriers: what we learned and what’s next

The project provided many valuable lessons for moving forward through the workshops attended by active and enthusiastic students and teachers. They demonstrated special strengths and insight into how to develop schools, offering constructive solutions to support safety and wellbeing in schools, while noting that implementing the solutions requires knowledge, understanding and careful planning. These efforts were supported by ongoing peer learning and multidisciplinary collaboration throughout the project.

The project introduced a new way of working, Appreciative Inquiry, which builds on the strengths and opportunities of the participants. In the workshops, the participants’ understanding and skills related to school work improved. They learned to find solutions to challenging situations and to envision a positive future. These skills can be applied to everyday life and even developed further with the methods of participation and community building. The teachers pointed out that thanks to the project they have managed to involve the students all the way from planning to reflecting on the activities. The students have taken on more responsibility, which requires a stronger commitment to their schoolwork. Additionally, language awareness has become an important part of teaching and activities at all levels of education.

Through this project, all participants deepened their understanding of how schools can become safe places for learning and growth. Now, it is up to each of us to put this knowledge into action and continue building environments where every learner can thrive.

References

Alajoki, J. 2021. Miks tää systeemi ei toimi? Etnografia inkluusiota kohti kulkevasta yläkoulusta. Tampereen yliopisto.

Bushe, G. 1999. Advances in Appreciative Inquiry as an organization development intervention. Organization Development Journal, 17 (2), 61.

Cooperrider, D., Srivastva, S. 1999. Appreciative Inquiry in organizational life. Appreciative management and leadership. Euclid, OH: Lakeshore Communications. 401–444.

Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D. & Kaplin, D. 2005. A Positive Revolution in Change. San Fransisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D. & Stravos, J. 2008. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook. For Leaders of Change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Edmondson, A. 1999. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly. 44 (2), 350–383.

Hammond, S. 2013. The thin book of appreciative Inquiry. Thin Book Publishing Company.

Heikkinen, H., Salo, P., Kaukko, M., Kiilakoski, T., Huttunen, R. Mutanen, A., Friman, M. & Nuutinen, L. 2023. Suuntauksia ja tulkintoja. Teoksessa Heikkinen, H. & Kaukko, M. (Eds.). Toimintatutkimus – Käytännön opas. Tampere: Vastapaino, 67–110.

Hollnagel, E. 2014. Is safety a subject for science? Safety Science 67, 21–24.

Ihamäki, K. & Nuutinen, L. 2024. Inkluusio ja turvallisuutta vahvistava yläkoulu. Metropolia Ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisuja, Taito-sarja 138. Helsinki: Metropolia University of Applied Sciences.

van Manen, M., & Li, S. 2002. The pathic principle of pedagogical language. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(2), 215–224.

Peleman, B., Lazzari, A., Budginaite, I., Siarova, H., Hauari, H., Peeters, J. & Cameron, C. 2018. Countinuous professional development and ECEC quality: findings from a European systematic literature review. European Journal of Education, 53(1), 9–22.

Reed, J. 2007. Research for change: ways to go. In Appreciative Inquiry. SAGE Publications, Inc., 178–202.

Saariaho, M. 2023. Self-competencies and Craft Agency. A Grounded Theory Study of Learning and Teaching Craft-Art. Väitöskirja. Kasvatustieteellisiä tutkimuksia 172. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto.

The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education 1994.

Salas, E., Burke, C., & Cannon-Bowers, J. 2003. Teamwork: emerging principles. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2(4), 339–356.

Sirkko, R., Takala, M. & Muukkonen, H. 2020. Yksin opettamisesta yhdessä opettamiseen: Onnistuneen yhteisopetuksen edellytykset. Kasvatus & Aika 14(1), 26–43.

World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality; final report. 1994. UNESCO.

Whitney D., Torsten-Bloom A. 2010. Eight Principles of Appreciative Inquiry. In: The Power of Appreciative Inquiry: Practical Guide to Positive Change. San Francico, CA: Barret-Koehler Publishers, 49–75.

Vitka, T. 2021. Laaja-alaisen erityisopetuksen käsikirja. Jyväskylä: PS-kustannus.

Authors

-

Katja Ihamäki

Senior Lecturer, Metropolia UASKatja Ihamäki, PhD, works as a senior lecturer in social science at the School of Wellbeing. In addition, she has been a project manager and expert in local and international RDI projects at Metropolia University of Applied Sciences.

About the author -

Liisa Nuutinen

Senior lecturer, Metropolia University of Applied SciencesMaster of Health Sciences and PhD student Liisa Nuutinen works as a senior lecturer in Sustainable Leadership and Development in Social and Health Care, a Master of Health Care degree programme at Metropolia UAS.

About the author